The UCOVI Blog

The UCOVI Blog

First-hand insights on data governance in the world of politics

Ned Stratton: 2nd September 2022

Part 1 - MERLIN

To coincide with the imminent conclusion of Truss vs Sunak (Rooney vs Vardy but lacking the self-awareness and economic policy grasp), and to show that the use of data in political campaigning is often far too cackhanded to be as sinister as Cambridge Analytica and Brexit/Trump, I thought I'd put pen to paper on data practices I observed in my 8 months as a first-line IT support guy at the HQ of the Conservative Party in 2014-15.

My first real job in data came just after this as a Database Officer (sadly no police sheriff's badge) in the marketing function of an exhibitions and training company, and I allude to the sort of work I'd go onto do there in my interview with Matt Childs last year. But I consider my short stint on the IT helpdesk at Tory HQ as the foundation year of my data career. It was here that I picked up a wealth of insights into what could go wrong in data management, database design, and software rollouts.

First, some context on what constitutes the data assets held by major UK political parties, their use cases, and their data governance obstacles.

The Conservatives (as of 2015 but I don’t imagine this has changed much), Labour and the Lib Dems hold these datasets:

- The UK Electoral Roll – this is the names, postal addresses, wards (local representation areas which roll up to Parliamentary constituencies for general elections), and polling numbers (a person-level unique identifier) of everyone in the UK who is registered to vote. Think of this as a bare-boned contact database of 45-50 million people.

- The marked register – this is a record for each local or general election of who has voted (not who they voted for, just that they voted).

- Membership and donation records – contact data on who is a member of said political party and how long they have been so (important for leadership elections – in the case of the Conservatives only members of at least 3 months of tenure can vote).

- Canvass returns and internal survey results – party activists hit the phones or go door to door asking if you'll vote for them and other things like "All other considerations aside, would our Kier Starmer make a better leader than Boris Johnson?". They log your answers against your electoral roll record and enter it into their data.

- Other useful titbits of data they find out about you on your doorstep during canvassing, such as whether you or those you live with are dead, and if not, what nicknames you go by. I will return to this.

- Telephone numbers – these can be purchased digitally from phone directories or data brokerages and matched against electoral roll records, along with info on whether the holder of the phone number has signed up to the Telephone Preference Service (TPS), which opts them out of cold calling.

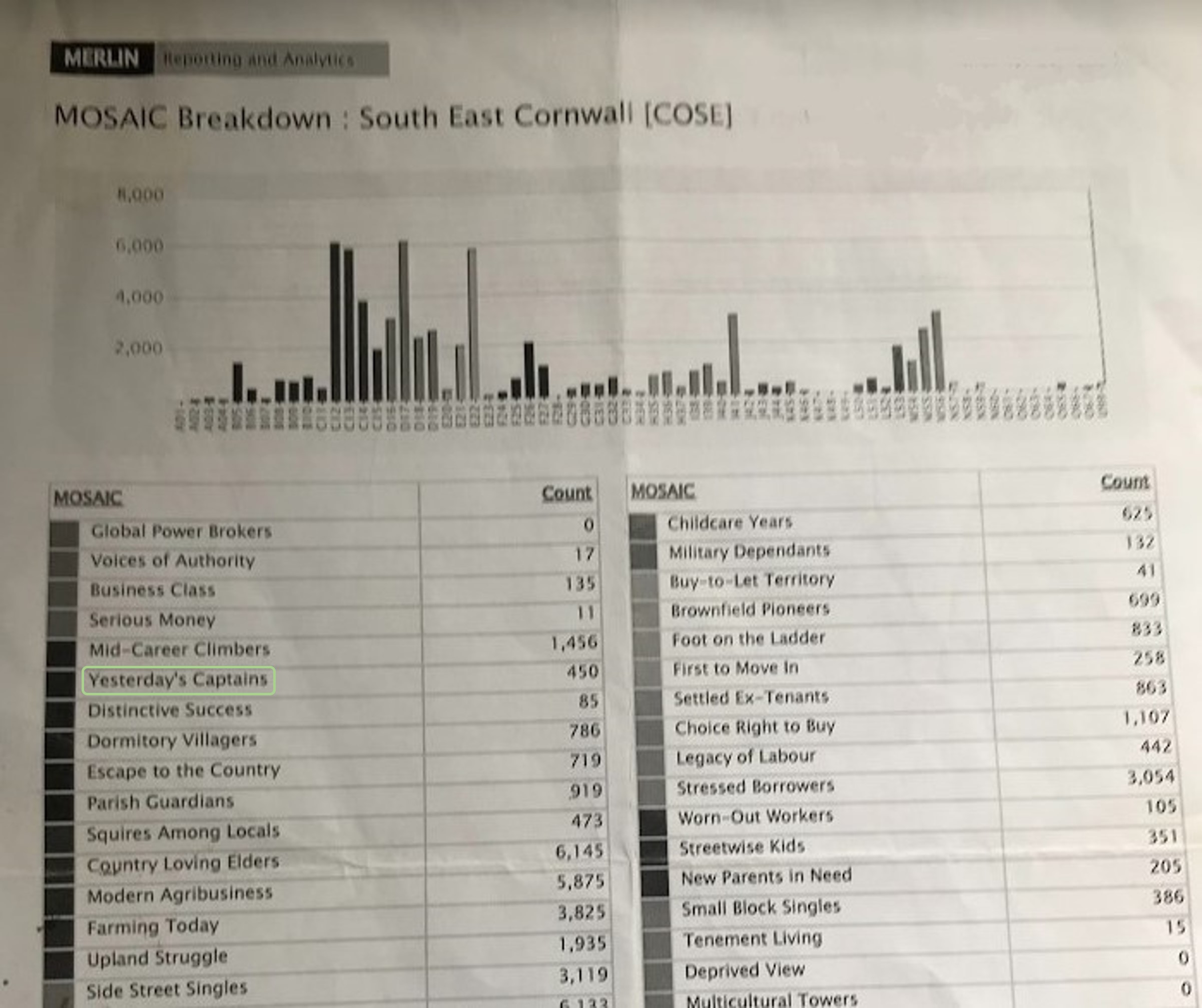

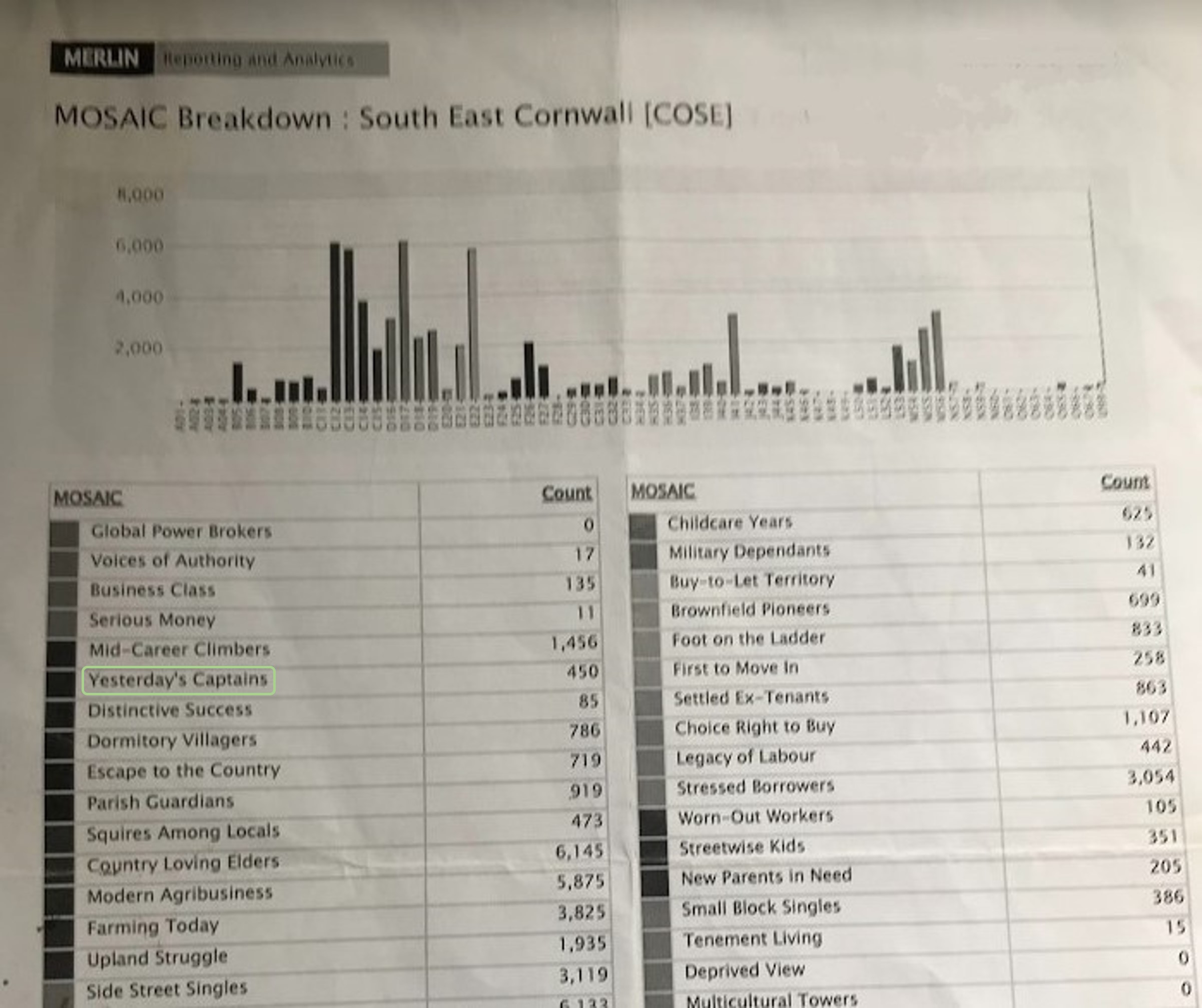

- Finally, algorithm-generated demographic categorisation, such as Experian Data's MOSAIC Codes. Experian built these personas from postcode data, credit scores, age range, purchasing history and more, and as of 2015 the Conservative Party were tagging people on the electoral roll as "Yesterday's Captains", "Worn-Out Workers", "Stressed Borrowers" and other such peculiar groupings thrown up among the 60-ish MOSAIC codes.

With all this data, the Conservatives and their rival parties aim to win elections and grow their membership base by finding out the following:

- Who voted for them last time and whether they intend to do so now.

- Who could vote for them this time based on them belonging to a social group that would benefit from their policies.

- On polling day itself, who said they'd vote for them this time but haven't turned up to vote yet, so that they can be given a lift to their nearest polling station.

- Who wants to vote for them so badly they could be convinced to become a member or donate.

In doing this, the Conservatives and their opponents face these challenges:

- Budget: They are voluntary organisations funded by membership subs and donations, and as such can’t swing their big data cocks around like a FAANG company by rigging up an enormous data centre in Texas or paying six figures to data scientists.

- Timing: general election campaigns are six-week bursts of activity that only occur once every 3-5 years, so staff and volunteers are short-term recruits hastily and patchily trained on the voter database and how to canvass from it.

- End-users: the data is input by volunteers who, especially in the case of the Conservative Party, are aging and impatient with computer software and smart-phone apps especially if - see directly above – these software apps are coded on the cheap and they haven't been trained properly.

- The data itself: First, the marked register comes in PDF so is time consuming to enter manually. Second, the UK Electoral Roll is updated each year to reflect newly registered voters, and as part of this update everyone's polling number (the primary key against which marked register data and election-day live voter turnout data are stored) is replaced and overwritten. This presents voter database managers with the unenviable task of reloading 50 million contact records every year and getting them to fuzzy match with pinpoint accuracy to existing records on name and address. The Conservative HQ IT and data teams referred to this process as the dreaded rollover.

With the context now set, may I introduce MERLIN, the custom-built database and data management software that the Conservatives were using to solve the problems outlined above as of 2014 when I arrived as an impressionable IT helpdesker with a passion for Excel VLOOKUPs.

Its processing speed was as slow as a knight of the round table moving around in full chain mail and helmet, but no, MERLIN was not named after the mythical wizard in the legend of King Arthur. It was actually an acronym of "Managing Electoral Relationships through Local Information Networks".

This lofty paradigm underpinned its network architecture. MERLIN was a central database server under the control of Party HQ in London that held the full national electoral roll, canvassing and membership data. This shared a computer network with 600-odd mini-servers in each constituency, which were Windows XP computers in the constituencies' offices hosting just that constituency's records. Data changes made nationally (HQ data team uploading the latest electoral roll or MOSAIC codes) would replicate across the network to the constituencies on a nightly basis with their cuts of the data, and constituency-made local updates (canvass-data entry) would all replicate back to the central database on the same frequency.

The supposed benefits of doing it like this were data minimisation (local volunteers and organisers would see only their constituency's data), as well as avoiding the cost of hosting a powerful enough database server for central analysts and local organisers to run query operations on the same database at the same time. Given the record count of the main table was never greater than 60 million and that the user base was around 4,000 admins, organisers and volunteers, I can only speculate that the Conservatives were more severely cash-strapped than reported in their wilderness years of the noughties when MERLIN was first commissioned.

The flaw of this design was the control (or lack thereof) that local organisers had over their MERLIN PCs. Working part-time and keen to keep the bills down, they would switch everything off at their constituency offices when vacated, thereby disconnecting their MERLIN PC from the network so that updates couldn't be replicated. Other interesting approaches to database administration and server management by regional Tory party activists included one constituency "losing" their MERLIN PC before a by-election with no explanation forthcoming, or as was discovered during remote IT support from HQ, using the PC to browse porn sites.

End users struggled equally badly with MERLIN taxonomy. Voting intentions recorded against constituents' records were a picklist choice of the minor political parties plus Undecided, Strong Labour, Weak Labour, Strong Conservative, and Weak Conservative, with the detailed categories for Labour/Conservative designed to identify shallow support that needed firming up and flaky opponents open to persuasion. Intended to be recorded from actual doorstep conversations, this voting intention taxonomy was used liberally by local organisers to the extent that one activist in a target seat tagged as Weak Conservative – in the words of their colleague during a phone call I had with them – "basically anyone in the constituency who owns a Lexus".

Similar creative guesswork was applied by activists canvassing over the phone, with some thinking the "TPS" tag next to opt-out phone numbers meant not "Telephone Preference Service" but instead "Tory Party Supporter".

At some point over the course of all this, and other episodes including system crashes during an important by-election in 2013 and an electoral roll data update in 2014 that went so badly on MERLIN that HQ resorted to sending the data in hard copy to the constituencies for manual data entry, the Conservative high command felt enough was enough. A new, cloud-era database and app was commissioned to take over from MERLIN as the Conservative Party's campaigning database in time for the 2015 General Election.

But would the new software shine brighter and prove up to the task of blending the UK electoral roll, canvass data and MOSAIC codes into an election-winning data asset for the Tories? Just like the winner of Truss vs Sunak, the answer to this question will be revealed next week, when I cover MERLIN's replacement – Votesource – in part 2.

⌚ Back to Latest Post